12.1 Introduction

This lecture introduces pipelining as the primary performance enhancement technique in modern processor design, transforming the inefficient single-cycle architecture into a high-throughput execution engine. We explore how pipelining applies assembly-line principles to instruction execution, dramatically improving processor throughput while maintaining individual instruction latency. The lecture examines the three fundamental types of hazards—structural, data, and control—that threaten pipeline efficiency, and discusses practical solutions including forwarding, stalling, and branch prediction that enable real-world pipelined processors to achieve near-ideal performance.

12.2 Recap: Single-Cycle Performance Limitations

12.2.1 Critical Path Problem

Load Word as Bottleneck:

- Uses most resources: Instruction Memory → Register File → ALU → Data Memory → Register File

- Determines clock period for entire CPU

- Forces all other instructions to wait

Performance Issue:

- Most instructions (arithmetic, branch) take less time than load

- Jump instruction takes even less time

- Clock period set by slowest instruction (load word)

Design Principle Violated:

- "Make the common case fast"

- Common case (arithmetic) forced to run slowly

- Majority of instructions underutilize available time

12.2.2 Multi-Cycle as First Improvement

Basic Concept:

- Divide datapath into stages

- Each stage completes in one clock cycle

- Shorter clock cycles than single-cycle

Five Stages Identified:

- Instruction Fetch (IF)

- Register Reading

- ALU Operations

- Memory Access

- Register Writing

Variable Stage Usage:

- Load: Uses all 5 stages

- Most instructions: Skip memory access (4 stages)

- Jump: Only 2 stages (manipulating PC)

Clock Period Determination:

- Decided by slowest stage (not slowest instruction)

- Adjust work in each stage for balance

- Maximize utilization of each clock cycle

Limitation:

- Instruction must finish before next instruction starts

- Hardware still idle during many cycles

- Room for further improvement

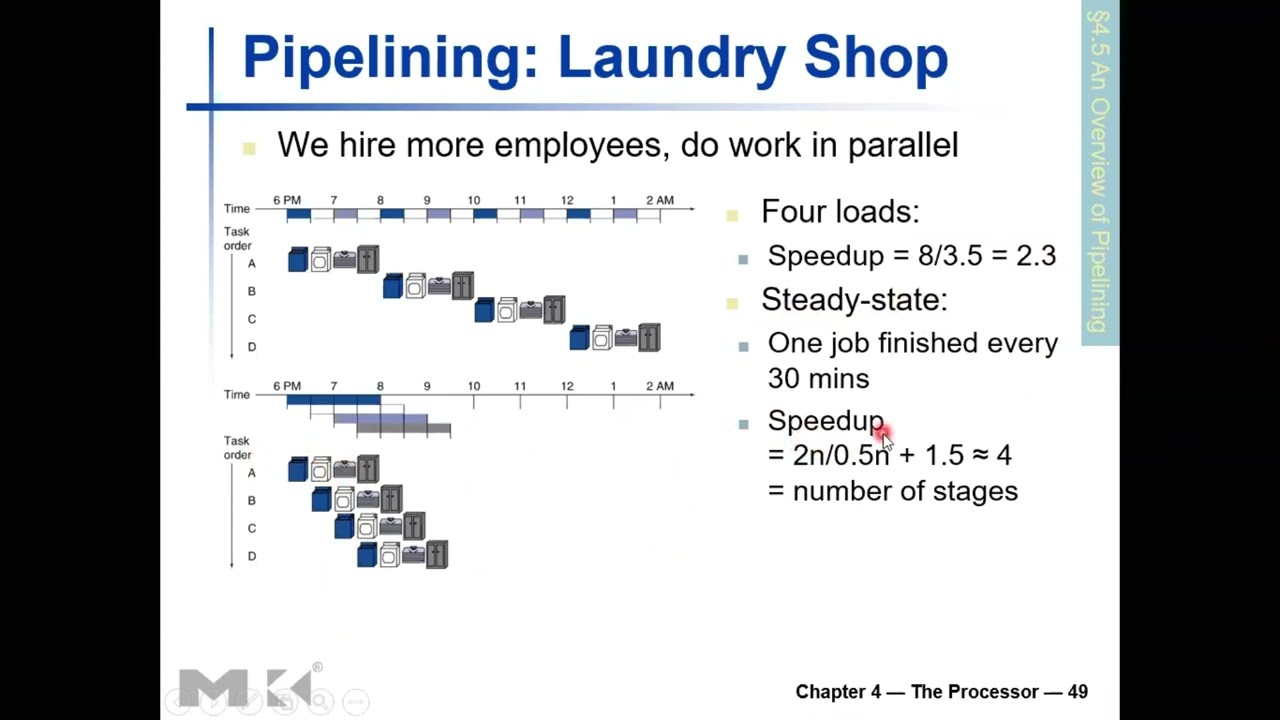

12.3 Pipelining Concept: The Laundry Shop Analogy

12.3.1 Non-Pipelined Laundry Shop

Setup:

- One employee

- Four customers: A, B, C, D

- First-come, first-serve basis

- Four stages of work per customer:

- Washing: 30 minutes

- Drying: 30 minutes

- Folding/Ironing: 30 minutes

- Packaging: 30 minutes

- Total per customer: 2 hours

Sequential Processing:

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Time | 8 hours (6pm to 2am) |

| Time per Customer | 2 hours |

| Shop Closes | 2am |

Problems:

- Machines idle while employee works on other stages

- Washer idle during drying, folding, packaging

- Dryer idle except during drying stage

- Tremendous resource underutilization

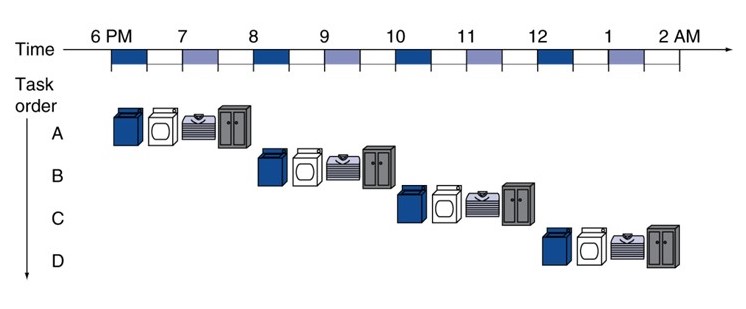

12.3.2 Pipelined Laundry Shop

Key Idea:

- Use idle machines for next customers

- Overlap execution of different loads

- Parallel processing maximizes hardware utilization

Pipelined Schedule:

Timeline Analysis:

- 6:00-6:30: A washing (1 station busy)

- 6:30-7:00: A drying, B washing (2 stations busy)

- 7:00-7:30: A folding, B drying, C washing (3 stations busy)

- 7:30-8:00: A packing, B folding, C drying, D washing (4 stations - ALL BUSY!)

- 8:00-8:30: A done, B packing, C folding, D drying, E washing

Steady State:

- Reached at 7:30-8:00 when all 4 stations occupied

- Pipeline full

- Maximum hardware utilization

- One customer finishes every 30 minutes

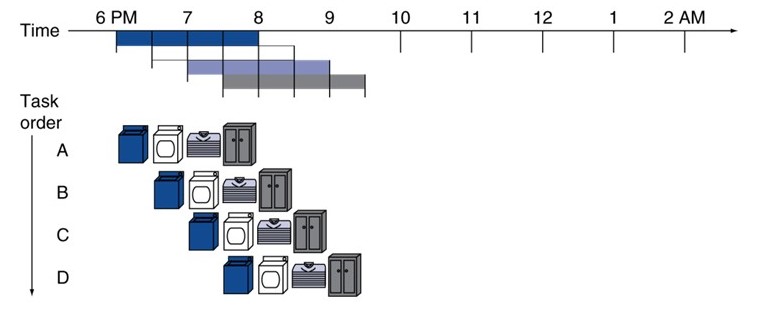

12.3.3 Performance Analysis

Time Comparison:

- Non-pipelined: 8 hours for 4 customers

- Pipelined: 3.5 hours for 4 customers

Speedup Calculation:

Speedup = Non-pipelined Time / Pipelined Time

= 8 hours / 3.5 hours

= 2.3×

Includes Pipeline Fill Time:

- First 1.5 hours: Filling pipeline (not all stations busy)

- After 1.5 hours: Steady state (all stations busy)

Steady State Analysis (ignoring fill time):

Non-pipelined: 2n hours for n loads (2 hours per load)

Pipelined: 0.5n hours for n loads (0.5 hours per load)

Steady State Speedup = 2n / 0.5n = 4×

Theoretical Maximum Speedup:

- Equals number of stages

- 4 stages → 4× speedup maximum

- 8 stages → 8× speedup maximum (if achievable)

12.3.4 Key Performance Terms

Latency:

- Time to complete one individual job

- Customer A: Still 2 hours in both cases

- Per-instruction time unchanged

Throughput:

- How often one job completes

- Non-pipelined: 1 job every 2 hours

- Pipelined: 1 job every 30 minutes (steady state)

- Throughput is the relevant metric for pipelines

Observation:

- Pipelining doesn't reduce individual job latency

- Pipelining dramatically improves throughput

- Overall system performance greatly enhanced

Analogy Summary:

- Customers = Instructions

- Stages = Pipeline stages

- Time saved = Performance improvement

- Overlapping execution = Instruction-level parallelism

12.4 MIPS Five-Stage Pipeline

12.4.1 Pipeline Stage Definitions

Stage 1: Instruction Fetch (IF)

- Use current Program Counter (PC)

- PC points to next instruction to execute

- Access instruction memory

- Fetch instruction word

- Duration: One clock cycle

Stage 2: Instruction Decode / Register Read (ID)

- Decode opcode field

- Determine instruction category

- Identify remaining bit organization

- Extract register addresses

- Read register file

- Both operations in one stage (workload balancing)

Stage 3: Execution (EX)

- Arithmetic/Logic instructions: ALU computes result

- Memory instructions: ALU computes address (base + offset)

- Branch instructions: ALU performs comparison

- One clock cycle

Stage 4: Memory Access (MEM)

- Load instructions: Read from data memory

- Store instructions: Write to data memory

- Other instructions: Skip this stage

- One clock cycle

Stage 5: Write Back (WB)

- Write result to register file

- Source: ALU result (arithmetic) OR memory data (load)

- Multiplexer selects appropriate source

- One clock cycle

Workload Distribution Goal:

- Evenly distribute work across stages

- Minimize clock cycle time

- Maximize hardware utilization

12.4.2 Stage Timing Example

Assumed Component Delays:

| Component | Delay (picoseconds) |

|---|---|

| Instruction Fetch | 200 ps |

| Register Read/Write | 100 ps |

| ALU Operation | 200 ps |

| Data Memory Access | 200 ps |

| Sign Extension | negligible |

| Multiplexers | negligible |

Single-Cycle Instruction Times:

| Instruction Type | Stages Used | Total Time |

|---|---|---|

| Load Word (LW) | IF+ID+EX+MEM+WB | 800 ps |

| Store Word (SW) | IF+ID+EX+MEM | 700 ps |

| R-type (ADD, etc.) | IF+ID+EX+WB | 600 ps |

| Branch (BEQ) | IF+ID+EX | 500 ps |

12.4.3 Pipeline Implementation Details

Clock Cycle Determination:

- Must accommodate longest stage

- Longest stage: 200 ps (IF, ALU, MEM)

- Clock cycle: 200 ps

- Some stages underutilize cycle (register read/write: 100 ps)

Register Read/Write Timing:

- CRITICAL: Register write first half, read second half of same clock cycle

- Enables same-cycle read-after-write

- Prevents data hazards in some cases

Stage Alignment to Clock Cycles:

| Stage | Work | Time | Cycle Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| IF | Instruction Memory read | 200 ps | 200 ps ✓ |

| ID | Decode + Register Read | 100 ps | 200 ps (space left) |

| EX | ALU operation | 200 ps | 200 ps ✓ |

| MEM | Data Memory access | 200 ps | 200 ps ✓ |

| WB | Register write | 100 ps | 200 ps (first half only) |

Space in ID Stage:

- Register read: 100 ps

- Decoding: Fits in remaining 100 ps

- Combinational logic for opcode decode

- Total: ~200 ps utilized

Space in WB Stage:

- Register write: 100 ps (first half)

- Second half: Available for next instruction's register read

12.4.4 Load Word Pipeline Example

Instruction Stream: All Load Word instructions

LW $1, 0($10)

LW $2, 4($10)

LW $3, 8($10)

LW $4, 12($10)

...

Pipeline Timing Diagram:

Time (ps): 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000 1000-1200

LW $1: IF ID EX MEM WB

LW $2: IF ID EX MEM WB

LW $3: IF ID EX MEM

LW $4: IF ID EX

Single-Cycle Comparison:

- Non-pipelined: 800 ps per instruction

- Pipelined: 200 ps per instruction (after pipeline fills)

Throughput Improvement:

Non-pipelined: 1 instruction every 800 ps

Pipelined: 1 instruction every 200 ps

Speedup = 800 / 200 = 4×

Absolute Time per Instruction:

- Still ~800 ps (slightly more with alignment overhead)

- Latency unchanged or slightly worse

- Throughput dramatically improved

12.4.5 Ideal vs Actual Speedup

Ideal Case (balanced stages):

Time between instructions (pipelined) = Time per instruction (non-pipelined) / Number of stages

Maximum Speedup = Number of Stages

Actual Implementation:

- Stages not perfectly balanced

- Register operations faster than memory/ALU

- Speedup < Number of stages

- Example: 5 stages → 4× speedup (not 5×)

Reasons for Less Than Ideal:

- Unbalanced stage delays

- Pipeline fill time overhead

- Hazards (discussed later)

- Added synchronization logic

12.5 MIPS ISA Design for Pipelining

12.5.1 Fixed Instruction Length

MIPS Characteristic:

- All instructions exactly 32 bits

- Same as ARM (also designed for pipelining)

Benefits for Pipelining:

- Simple instruction fetch (always 32 bits)

- Simple decode (fixed format)

- Bus width fully utilized every time

- No variable-width handling logic

Alternative (Variable-Length):

- Complicates fetch stage

- Requires width detection logic

- May need multiple fetch cycles

- Added combinational logic delays

12.5.2 Fewer Regular Instruction Formats

MIPS Formats:

- Only 3-4 instruction formats (R, I, J types)

- Small opcode field (6 bits)

- Regular register field positions

Benefits:

- Fast decoding (small opcode → simple logic)

- Fits decode + register read in one stage

- Minimal combinational delay

Register Field Consistency:

- RS (bits 21-25): First source register

- RT (bits 16-20): Second source / destination

- RD (bits 11-15): Destination (R-type)

- Same positions across formats

Decoding Simplification:

- Small opcode → simple decode logic

- Regular formats → minimal mux complexity

- Fast enough for single clock cycle

12.5.3 Separate ALU Operation Field

Function Field (funct):

- Bits 0-5: Specifies ALU operation for R-type

- Separate from opcode

- Only examined for R-type (opcode = 0)

Design Rationale:

- ALU operation determined in EX stage

- Opcode used in ID stage

- Temporal separation matches pipeline stages

Benefit:

- funct field processed later (EX stage)

- Opcode processed early (ID stage)

- Separating them simplifies each stage

- Avoids large opcode (keeps decode simple)

Alternative Design:

- Include funct in opcode

- Larger opcode field needed

- More complex decode logic

- Slower ID stage

- Worse pipeline balance

12.5.4 Load/Store Addressing Mode

MIPS Addressing:

- Base register + offset

- Address = $rs + immediate

- Calculation: Simple addition

Pipeline Fit:

- Address calculation: EX stage (ALU)

- Memory access: MEM stage (next cycle)

- Clean separation into two stages

Design Philosophy:

- ISA designed with pipeline in mind

- Not optimized for single-cycle

- Performance through pipelining

MIPS vs Other ISAs:

- MIPS: Designed for pipelining from start

- x86: Complex instructions, harder to pipeline

- ARM: Similar philosophy to MIPS

- RISC principles support pipelining

12.6 Instruction-Level Parallelism (ILP)

12.6.1 Parallel Execution Concept

Definition:

- Multiple instructions executing simultaneously

- Each at different pipeline stage

- Overlapping execution

Example at Steady State:

Time Window: 800-1000 ps

Instruction A: WB stage (writing result)

Instruction B: MEM stage (memory access)

Instruction C: EX stage (ALU operation)

Instruction D: ID stage (decode, register read)

Instruction E: IF stage (fetch)

Five instructions active simultaneously!

Instruction-Level Parallelism (ILP):

- Lowest granularity of parallelism

- Inside CPU microarchitecture

- Transparent to software

- Hardware manages parallelism

12.6.2 Levels of Parallelism

Instruction-Level Parallelism:

- Multiple instructions in pipeline

- Same program/thread

- Within CPU core

- Microsecond/nanosecond scale

Thread-Level Parallelism:

- Multiple threads on same core

- Context switching

- OS-managed

- Millisecond scale

Program-Level Parallelism:

- Multiple programs/processes

- Multi-core execution

- OS-scheduled

- Varied time scales

Application-Level Parallelism:

- Distributed computing

- Multiple machines

- Network communication

- Seconds to minutes scale

ILP Focus:

- Fine-grained parallelism

- Hardware implementation

- Transparent to programmer (mostly)

- Foundation for all higher levels

12.7 Pipeline Hazards: Structural Hazards

12.7.1 Hazard Definition

General Concept:

- Situations preventing next instruction from starting

- Violates basic pipelining goal

- Reduces throughput

- Requires pipeline stalls (bubbles)

Three Categories:

- Structural Hazards: Hardware resource busy

- Data Hazards: Need data from previous instruction

- Control Hazards: Decision depends on previous result

12.7.2 Structural Hazard: Single Memory

Scenario:

- Single memory device for both instructions and data

- No separate instruction/data memory

- Same device holds program and data

Conflict Example:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800

LW $1: IF ID EX MEM

LW $2: IF ID EX

LW $3: IF ID

LW $4: IF ← CONFLICT!

At 600-800 ps:

• LW $1 needs data memory (MEM stage)

• LW $4 needs instruction memory (IF stage)

• Same physical memory device!

• Cannot access simultaneously

Problem:

- Memory can only service one request per cycle

- Instruction fetch AND data access conflict

- Hardware resource (memory) busy

12.7.3 Pipeline Stall (Bubble)

Solution: Insert Bubble

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000 1000-1200

LW $1: IF ID EX MEM WB

LW $2: IF ID EX [BUBBLE] MEM

LW $3: IF ID EX [BUBBLE]

LW $4: IF [BUBBLE] ID

Bubble Characteristics:

- No instruction in that pipeline stage

- Like air bubble in water pipeline

- Hardware idle for that stage

- Wastes one clock cycle

- Propagates through pipeline stages

Impact:

- One instruction delayed

- Subsequent instructions delayed

- Throughput reduced

- Performance loss

Bubble Analogy:

- Water pipeline: Continuous flow

- Air bubble: Break in flow

- Takes time to propagate through

- Reduces effective flow rate

12.7.4 Solutions to Structural Hazards

Solution 1: Separate Memories

- Instruction memory separate from data memory

- Harvard architecture

- Simultaneous access possible

- No structural hazard

Solution 2: Separate Caches

- Single main memory

- Separate instruction cache (I-cache)

- Separate data cache (D-cache)

- Cache: Fast buffer between CPU and memory

- Caches can be accessed simultaneously

- Details in future lectures (memory hierarchy)

Design Recommendation:

- Modern processors use separate caches

- Necessary for high-performance pipelining

- Small area overhead for large performance gain

12.8 Data Hazards

12.8.1 Data Hazard Definition

Concept:

- Subsequent instruction needs data from previous instruction

- Data not yet available (still being computed/written)

- Reading too early → wrong value

- Writing too early → data corruption

Example:

ADD $s0, $t0, $t1 # $s0 = $t0 + $t1

SUB $t2, $s0, $t3 # $t2 = $s0 - $t3 (uses $s0 from ADD)

Problem:

- ADD computes $s0 value in EX stage

- SUB needs $s0 value in ID stage (register read)

- Timing mismatch

12.8.2 Data Hazard Example Analysis

Instruction Sequence:

ADD $s0, $t0, $t1

SUB $t2, $s0, $t3

Pipeline Without Stalls:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000

ADD: IF ID EX MEM WB

SUB: IF ID EX MEM

↑

Reads $s0 here (old value!)

ADD writes $s0 here ↓

Problem Timeline:

- 200-400: ADD reads $t0, $t1; SUB fetched

- 400-600: ADD computes in ALU; SUB reads registers (gets OLD $s0!)

- 600-800: ADD result available but not in register yet

- 800-1000: ADD writes $s0 to register (first half of cycle)

SUB reads $s0 at 400-600, but correct value not available until 800-1000!

12.8.3 Solution 1: Pipeline Stalls

Insert Two Bubbles:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000 1000-1200 1200-1400

ADD: IF ID EX MEM WB

[BUBBLE] IF [BUBBLE] [BUBBLE]

[BUBBLE] IF [BUBBLE]

SUB: IF ID

Result:

- SUB fetched at 1000-1200

- SUB reads registers at 1200-1400 (second half at 1200)

- ADD writes $s0 at 800-1000 (first half at 800)

- Sufficient time gap: Correct value available

Cost:

- Two clock cycles wasted

- Throughput reduced

- Performance penalty

Critical Timing:

- Register write: First half of WB cycle

- Register read: Second half of ID cycle

- Enables back-to-back reading of just-written value

12.8.4 Solution 2: Forwarding (Bypassing)

Key Observation:

- ADD result available after EX stage (400-600)

- Result at ALU output

- Not yet written to register file

- But SUB's ALU operation at 600-800

- Can forward ALU output directly to ALU input!

Forwarding Logic:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000

ADD: IF ID EX MEM WB

SUB: IF ID EX MEM

↑ ↑

Read regs Use forwarded value!

Implementation:

- Multiplexer at ALU input

- Selects between:

- Register file output (normal path)

- Forwarded value from previous ALU output

- Control logic detects dependency

- Routes correct value

Benefit:

- Eliminates two stalls

- No performance penalty

- Requires additional hardware:

- Forwarding multiplexers

- Forwarding detection logic

- Forwarding paths (wires)

- Pipeline registers to hold values

Complexity:

- Careful synchronization required

- Detect true dependencies

- Avoid false positives

- Additional control signals

Result:

- SUB can execute immediately after ADD

- No stalls needed

- Correct value forwarded

12.8.5 Load-Use Data Hazard

Special Case:

LW $s0, 0($t0) # Load from memory into $s0

SUB $t2, $s0, $t3 # Use $s0 immediately

Problem:

- Load result available after MEM stage (data from memory)

- SUB needs value in EX stage

- Even forwarding can't help!

Timeline:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000

LW: IF ID EX MEM WB

SUB: IF ID EX MEM

↑ ↑

Need value Value first available here!

LW result available at 600-800, but SUB's EX at 600-800 (simultaneous!)

Unavoidable Stall:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800 800-1000 1000-1200

LW: IF ID EX MEM WB

[BUBBLE] IF [BUBBLE] ID

SUB: IF ID

One stall bubble required:

- Cannot be eliminated by forwarding

- Can forward from MEM to EX (saves one stall vs two)

- But at least one stall unavoidable

12.8.6 Compiler Solution: Code Reordering

C Code Example:

a = b + e;

c = b + f;

Naive Assembly (Load-Use Hazards):

LW $t1, 0($t0) # Load b into $t1

LW $t2, 4($t0) # Load e into $t2

ADD $t3, $t1, $t2 # a = b + e ← HAZARD: uses $t2 immediately after LW

SW $t3, 8($t0) # Store a

LW $t4, 12($t0) # Load f into $t4

ADD $t5, $t1, $t4 # c = b + f ← HAZARD: uses $t4 immediately after LW

SW $t5, 16($t0) # Store c

Total: 7 instructions + 2 stalls = 9 clock cycles

Optimized Assembly (Reordered):

LW $t1, 0($t0) # Load b into $t1

LW $t2, 4($t0) # Load e into $t2

LW $t4, 12($t0) # Load f into $t4 ← Moved here!

ADD $t3, $t1, $t2 # a = b + e ← No hazard! $t2 available

SW $t3, 8($t0) # Store a ← Moved here!

ADD $t5, $t1, $t4 # c = b + f ← No hazard! $t4 available

SW $t5, 16($t0) # Store c

Total: 7 instructions + 0 stalls = 7 clock cycles

Technique:

- Load f earlier (between loading b and e)

- Fills stall slot with useful work

- Store a before second ADD (fills another gap)

- No bubbles needed

Compiler Responsibility:

- Analyze dependencies

- Reorder instructions safely

- Fill stall slots with independent instructions

- Maintain program semantics

Programmer Awareness:

- Understand pipeline behavior

- Write code amenable to reordering

- Separate dependent instructions when possible

- Help compiler optimize

12.9 Control Hazards

12.9.1 Control Hazard Definition

Concept:

- Branch/Jump outcome determines next instruction

- Decision depends on previous computation

- Can't fetch next instruction until decision made

- Pipeline must wait

Example:

BEQ $1, $2, target # Branch if $1 == $2

ADD $3, $4, $5 # Next sequential instruction

...

target: SUB $6, $7, $8 # Branch target

Which instruction to fetch after BEQ?

- ADD if branch NOT taken

- SUB if branch IS taken

- Decision requires comparison: $1 vs $2

12.9.2 Branch Execution in Pipeline

Branch Instruction:

BEQ $1, $2, 40 # Branch 40 instructions ahead if equal

Pipeline Stages:

- IF: Fetch BEQ instruction

- ID: Read $1, $2 from register file

- EX: ALU compares (subtract $2 from $1, check zero flag)

- Result available after EX stage

Problem:

- Next instruction fetch at cycle 2 (IF for next instruction)

- Branch outcome known at cycle 3 (after EX)

- Must guess which instruction to fetch!

Without Optimization:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800

BEQ: IF ID EX MEM

???: IF ???

Two bubbles required if wait for outcome

12.9.3 Solution 1: Early Branch Resolution

Add Hardware in ID Stage:

- Small adder for comparison

- Compute branch condition early (ID instead of EX)

- Subtract $1 - $2 in ID stage

- Parallel to register read

Modified Pipeline:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600

BEQ: IF ID EX

↑

Decision here!

Next: IF

Benefit:

- Decision after ID (one cycle earlier)

- Only one bubble needed (vs two)

- Better performance

Cost:

- Additional adder hardware

- Extra combinational logic in ID stage

- More complex ID stage

Limitation:

- Still one unavoidable stall

- Can't know outcome in same cycle as fetch

12.9.4 Solution 2: Branch Prediction

Static Branch Prediction:

- Guess branch outcome

- Fetch based on guess

- If correct: No penalty

- If wrong: Discard fetched instruction, fetch correct one

Strategy: Predict Not Taken

- Assume branch will NOT be taken

- Always fetch PC + 4 (sequential instruction)

- Proceed normally if correct

- Stall and correct if wrong

Example (Prediction Correct):

ADD $3, $4, $5

BEQ $1, $2, 14 # Actually NOT taken

LW $8, 0($9) # Fetch this (prediction: not taken)

Timeline:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800

ADD: IF ID EX MEM

BEQ: IF ID EX

LW: IF ID

↑ Fetched based on prediction

At 400-600 (after BEQ's ID):

- Determine branch NOT taken

- Prediction correct!

- LW continues normally

- No stall!

Example (Prediction Incorrect):

ADD $3, $4, $5

BEQ $1, $2, 14 # Actually IS taken

LW $8, 0($9) # Fetched (but shouldn't execute)

...

target: SUB $6, $7, $8 # Should execute this instead

Timeline:

Time: 0-200 200-400 400-600 600-800

ADD: IF ID EX MEM

BEQ: IF ID EX

LW: IF [DISCARD]

SUB: IF

BEQ: IF ID EX

LW: IF [DISCARD]

SUB: IF

`

At 400-600 (after BEQ's ID):

- Determine branch IS taken

- Prediction wrong!

- Discard LW (clear pipeline stage)

- Fetch SUB from branch target

- One bubble inserted

Result Analysis:

- Correct prediction: Save one cycle

- Incorrect prediction: Same as no prediction (one stall)

- Net benefit if prediction often correct

- No additional penalty for wrong guess

12.9.5 Static Branch Prediction Strategies

Simple Static: Always Predict Not Taken

- Fixed prediction

- Ignore branch type

- Ignore branch history

- Simple hardware

Program Behavior-Based Static:

- Analyze typical branch patterns

- Make predictions based on code structure

Backward Branches:

- Usually taken

- Example: Loops

loop:

...

BEQ $t0, $zero, loop # Backward branch

- Loop iterations: Branch taken many times

- Loop exit: Branch not taken once

- Prediction: Taken → Correct most of time

Forward Branches:

- Usually not taken

- Example: If statements

BEQ $t0, $zero, skip

... # True case

skip:

... # After if

- True case: Branch not taken

- False case: Branch taken

- Prediction depends on code style

Strategy: Backward Taken, Forward Not Taken

- 90%+ accuracy possible

- Based on empirical program analysis

- Requires code analysis

12.9.6 Dynamic Branch Prediction

Concept:

- Hardware learns branch behavior

- Predicts based on history

- Adapts to current code execution

- Not fixed prediction

Branch History Table:

- Hardware table storing recent branch outcomes

- Indexed by branch instruction address

- Each entry: Branch taken or not taken recently

- Predicts based on recent behavior

Simple 1-Bit Predictor:

- One bit per branch: Last outcome

- Predict same as last time

- Updates after each execution

Example:

Loop iteration 1: Taken → Predict taken next

Loop iteration 2: Taken → Predict taken next

...

Loop iteration 100: Taken → Predict taken next

Loop exit: Not taken → Predict not taken next (wrong for next loop!)

Problem: Wrong twice per loop (entry and exit)

2-Bit Saturating Counter:

- Two bits per branch: State machine

- Four states:

- 00: Strongly not taken

- 01: Weakly not taken

- 10: Weakly taken

- 11: Strongly taken

- Change prediction after two consecutive wrong predictions

- More stable

Advanced Predictors:

- Correlating predictors (look at multiple branches)

- Two-level adaptive predictors

- Tournament predictors (combine multiple algorithms)

- Very high accuracy (>95%)

Hardware Cost:

- Branch history table (memory)

- Prediction logic (comparators, counters)

- Update logic

- Worthwhile for performance gain

12.10 Summary and Key Concepts

12.10.1 Pipelining Benefits

Performance Improvement:

- Throughput increased by number of stages

- 5-stage pipeline → 4-5× speedup

- Latency unchanged or slightly worse

- Overlapping execution key

Hardware Utilization:

- All stages active in steady state

- Parallel processing

- Maximum efficiency

12.10.2 Pipeline Challenges

Hazards:

- Structural: Hardware resource conflicts

- Data: Instruction dependencies

- Control: Branch/jump decisions

Solutions:

- Structural: Separate memories/caches

- Data: Forwarding, stalls, code reordering

- Control: Early resolution, branch prediction

12.10.3 MIPS Design Philosophy

ISA Designed for Pipelining:

- Fixed 32-bit instruction length

- Regular instruction formats

- Separate funct field

- Simple addressing modes

- Balanced pipeline stages

Performance Through Hardware:

- Pipelining fundamental to MIPS

- Not optimized for single-cycle

- Hardware complexity for software simplicity

12.10.4 Key Takeaways

- Pipelining improves throughput, not latency

- Steady state determines peak performance

- Pipeline fill time overhead for small programs

- Hazards reduce pipelining efficiency

- Forwarding eliminates many data hazards

- Load-use hazard always requires one stall

- Branch prediction crucial for control flow

- Compiler optimization reduces stalls

- ISA design significantly impacts pipeline efficiency

- ILP fundamental to modern processor performance

12.11 Important Formulas and Metrics

Speedup Calculation

Speedup = Non-pipelined Time / Pipelined Time

Ideal Speedup = Number of Pipeline Stages

Actual Speedup = Number of Stages / (1 + Hazard Impact)

Throughput

Throughput = 1 instruction / Clock Period

Throughput Improvement = Clock Period (non-pipelined) / Clock Period (pipelined)

Pipeline Performance

Time = (Number of Instructions + Stages - 1) × Clock Period

CPI (Cycles Per Instruction) = 1 + Stall Cycles per Instruction

Effective CPI = 1 + (Structural Stalls + Data Stalls + Control Stalls)

Branch Prediction Accuracy

Accuracy = Correct Predictions / Total Branches

Stall Reduction = Accuracy × Cycles Saved per Correct Prediction

Key Takeaways

- Pipelining improves throughput, not latency—individual instructions take same or longer time, but more instructions complete per unit time.

- Five-stage MIPS pipeline: Instruction Fetch (IF), Instruction Decode (ID), Execute (EX), Memory Access (MEM), Write-Back (WB).

- Ideal speedup equals number of stages—five-stage pipeline theoretically achieves 5× speedup over single-cycle design.

- Assembly line analogy clarifies concept—like manufacturing, each stage works on different item simultaneously for maximum efficiency.

- Pipeline registers store intermediate results between stages, enabling independent operation and preventing data corruption.

- Three hazard types threaten pipeline efficiency: Structural (resource conflicts), Data (register dependencies), Control (branch/jump delays).

- Structural hazards resolved by hardware duplication—separate instruction and data caches eliminate memory access conflicts.

- Data hazards occur when instructions depend on previous results—forwarding (bypassing) allows ALU results to skip write-back stage.

- Forwarding paths connect pipeline stages directly, enabling result use before register file write completes.

- Load-use hazard requires one-cycle stall—memory data unavailable in time for immediate ALU use even with forwarding.

- Compiler code reordering can eliminate some stalls—moving independent instructions into load delay slots maintains pipeline flow.

- Control hazards arise from branch/jump instructions—don't know next PC until branch resolves in third cycle.

- Branch delay of 3 cycles in basic pipeline—fetch/decode/execute complete before decision known, wasting 3 instruction slots.

- Early branch resolution reduces penalty—dedicated comparison hardware in ID stage cuts delay to 1 cycle.

- Static branch prediction assumes direction (e.g., always not-taken)—simple but limited effectiveness.

- Dynamic branch prediction learns patterns from history—branch target buffer with 2-bit saturating counters achieves >90% accuracy.

- Two-bit counters prevent single misprediction disruption—requires two wrong predictions to change direction, handling loop patterns well.

- Pipeline performance = 1 CPI + Structural Stalls + Data Stalls + Control Stalls—minimizing hazards approaches ideal throughput.

- Modern processors use sophisticated prediction—multi-level predictors, pattern history tables, and return address stacks minimize control hazards.

- Pipeline complexity trades off with performance—deeper pipelines increase throughput but amplify hazard penalties and design difficulty.

Summary

Pipelining revolutionizes processor performance by applying manufacturing assembly-line principles to instruction execution, allowing multiple instructions to occupy different pipeline stages simultaneously. The five-stage MIPS pipeline (IF, ID, EX, MEM, WB) theoretically achieves 5× speedup by keeping all hardware components busy every cycle, transforming the inefficient single-cycle design where most hardware sat idle most of the time. However, three hazard types threaten this ideal performance: structural hazards from resource conflicts (solved by hardware duplication like separate instruction and data caches), data hazards from register dependencies (addressed by forwarding paths that bypass results directly between stages, though load-use cases still require one-cycle stalls), and control hazards from branches that don't resolve until the third cycle (mitigated by early branch resolution hardware, static prediction strategies, and sophisticated dynamic branch predictors using two-bit saturating counters that achieve over 90% accuracy). The effectiveness of forwarding demonstrates how careful hardware design can eliminate most data hazard stalls, while compiler optimizations like instruction reordering can fill remaining delay slots with useful work. Branch prediction evolution from simple static schemes to complex dynamic predictors with branch target buffers reflects the critical importance of minimizing control hazards in modern high-performance processors. Pipeline registers between stages serve as the crucial mechanism enabling independent stage operation, storing intermediate results and control signals while preventing data corruption across instruction overlaps. While pipelining introduces significant design complexity compared to single-cycle implementations, the dramatic performance improvements—approaching 5× speedup in practice—justify this added sophistication, making pipelining universal in modern processor architectures from embedded systems to supercomputers. Understanding these hazards and their solutions provides essential foundation for comprehending real-world processor implementations and the tradeoffs between pipeline depth, clock frequency, and hazard penalties that define contemporary computer architecture.