16.1 Introduction

This lecture explores advanced cache design techniques that significantly impact memory system performance. We examine write policies—specifically write-through and write-back strategies—understanding how each handles the critical challenge of maintaining consistency between cache and main memory while balancing performance and complexity. The lecture then progresses to associative cache organizations, from direct-mapped through set-associative to fully-associative designs, revealing how different levels of associativity affect hit rates, access latency, and hardware complexity. Through detailed examples and performance analysis, we discover how modern cache systems make strategic trade-offs between speed, capacity utilization, and implementation cost to achieve optimal memory hierarchy performance.

16.2 Recap: Write Access in Direct Mapped Cache

16.2.1 Write-Through Policy

- When a write access occurs, the cache controller determines if it's a hit or miss through tag comparison

- On a write hit: The block is in cache, update it. The cache copy becomes different from memory (inconsistent)

- Write-through solution: Always write to both cache and memory simultaneously

- On a write miss: Stall the CPU, fetch the missing block from memory, update the cache, and write to memory

16.2.2 Advantages of Write-Through

- Simple to implement - straightforward cache controller design

- Old blocks can be discarded without concern since memory is always up-to-date

- Can overlap writing and tag comparison operations since corrupted data can be safely discarded on a miss

16.2.3 Disadvantages of Write-Through

- Generates heavy write traffic to memory

- Every cache write triggers a memory write

- Bus between cache and memory can become congested

- Inefficient when programs have many store instructions

- CPU must stall for 10-100 clock cycles on each memory write

16.2.4 Write Buffer Solution

- A FIFO (First In First Out) queue between cache and memory

- Cache puts write requests in the buffer instead of directly to memory

- Memory processes requests from buffer at its own speed

- Allows CPU to continue without waiting for memory

- Works well for burst writes (short sequences of writes with gaps between)

- Limitation: If CPU generates continuous writes, buffer fills up and CPU must still stall

16.3 Write-Back Policy

16.3.1 Basic Concept

- Write to cache only, not to memory immediately

- Allow cache and memory to be inconsistent

- Write blocks back to memory only when evicted from cache

16.3.2 Dirty Bit

- An additional bit array in cache structure (alongside valid, tag, data)

- Tracks whether a cache block has been modified

- Set when block is written to cache

- Indicates that memory copy is not up-to-date

16.3.3 Write-Back Operations

On Write Hit:

- Simply update the cache entry

- Set the dirty bit to indicate inconsistency

- Do not write to memory

On Read Miss:

- Fetch missing block from memory

- If old block at that entry is dirty (dirty bit = 1):

- Write old block back to memory first

- Then fetch new block and overwrite

- If old block is not dirty:

- Directly fetch new block and overwrite

On Write Miss:

- If old block is dirty:

- Write old block back to memory

- Fetch new block from memory

- Update cache entry only (not memory)

16.3.4 Advantages of Write-Back

- Significantly reduces write traffic to memory

- More efficient when programs have many write accesses

- Cache is fast; only writing to cache most of the time

- Write buffer can be used for evicted dirty blocks

16.3.5 Disadvantages of Write-Back

- More complex cache controller

- Need to maintain and check dirty bit

- More hardware required

- More logic in controller design

16.3.6 Write-Back Cache Structure

- Data array

- Tag array

- Valid bit array

- Dirty bit array (new addition)

16.4 Cache Performance

16.4.1 Average Access Time Formula

T_avg = Hit Latency + Miss Rate × Miss Penalty

Where:

- Hit Latency: Time to determine a hit (always present)

- Miss Rate: 1 - Hit Rate (fraction of accesses that are misses)

- Miss Penalty: Time to fetch missing block from memory

- Can be expressed in absolute time (nanoseconds) or clock cycles

16.4.2 Example Calculation

Given:

- Miss Penalty = 20 CPU cycles

- Hit Rate = 95% (0.95)

- Hit Latency = 1 CPU cycle

- Clock Period = 1 nanosecond (1 GHz)

T_avg = 1 + (1 - 0.95) × 20

= 1 + 0.05 × 20

= 2 cycles

= 2 nanoseconds

If hit rate improves to 99.9%:

T_avg = 1 + (1 - 0.999) × 20

= 1 + 0.001 × 20

= 1.02 cycles

This shows significant improvement from better hit rate.

16.4.3 Performance Example Problem

Given:

- Program with 36% load/store instructions

- Ideal CPI = 2 (assuming perfect caches)

- Instruction cache miss rate = 2%

- Data cache miss rate = 4%

- Miss penalty = 100 cycles

Calculating Actual CPI:

- Stalls from instruction cache misses: I × 0.02 × 100 = 2I cycles

- Stalls from data cache misses: I × 0.36 × 0.04 × 100 = 1.44I cycles

- Total stall cycles: 3.44I

- Actual CPI = 2 + 3.44 = 5.44 cycles per instruction

CPI with no caches:

- Every instruction fetch: 100 cycles

- 36% need data memory: 0.36 × 100 = 36 cycles

- Total CPI = 2 + 100 + 36 = 138 cycles

- Slowdown without caches: 138 / 5.44 = 25.37×

16.5 Improving Cache Performance

16.5.1 Three Factors to Improve

- Hit Rate - increase the percentage of hits

- Hit Latency - reduce time to determine hits

- Miss Penalty - reduce time to fetch missing blocks

16.5.2 Improving Hit Rate

Method 1: Larger Cache Size

- More cache blocks means more index bits

- Reduces probability of multiple addresses mapping to same index

- Better exploitation of temporal locality

- Trade-off: Higher cost (SRAM is expensive, ~$2000 per gigabyte)

- Trade-off: More chip area required

16.5.3 Direct Mapped Cache Limitation

- Multiple memory blocks can map to same cache index

- Even with empty cache blocks elsewhere, conflicts cause evictions

- Temporal locality suggests recently accessed blocks should stay

- But direct mapping forces eviction even when space is available

16.6 Fully Associative Cache

16.6.1 Concept

- Eliminate index field - no fixed mapping

- A block can be placed anywhere in cache

- Address divided into: Tag + Offset (no index)

- Tag is larger since no index bits

16.6.2 Finding Blocks

- Cannot use index to locate block

- Sequential search is too slow

- Solution: Parallel tag comparison

- Compare incoming tag with all stored tags simultaneously

- Requires one comparator per cache entry

16.6.3 Implementation

- Need duplicate comparator hardware for each entry

- Practical only for small number of entries (8, 16, 32, 64)

- As entries increase: more comparators, longer wires, more delays

16.6.4 Block Placement

- Find first available invalid entry

- Use sequential logic to search for invalid bit

- Takes more time than direct mapped

16.6.5 Block Replacement

When all entries are valid, need replacement policy to choose which block to evict.

16.6.6 Replacement Policies

When all entries are valid, need replacement policy to choose which block to evict.

- LRU (Least Recently Used) - IDEAL:

- Evict the block that was used longest ago

- Best exploits temporal locality

- Very complex to implement

- Need to timestamp every access

- Expensive in hardware

- Pseudo-LRU (PLRU):

- Approximation of LRU

- Simpler mechanism than true LRU

- 90-99% of time picks least recently used

- Better balance of performance and complexity

- FIFO (First In First Out):

- Evict block that entered cache first

- Very simple implementation

- Only update when new block fetched (not on every access)

- Lower likelihood of picking LRU block

- Used in embedded systems for simplicity and low power

16.6.7 Fully Associative - Advantages

- High utilization of cache space

- Better hit rate (fewer conflict misses)

- Can choose replacement policy based on needs

16.6.8 Fully Associative - Disadvantages

- Block placement is slow (increases miss penalty)

- Higher power consumption

- Higher cost (more hardware)

- Parallel tag comparison requires duplicate hardware

16.7 Set Associative Cache

16.7.1 Concept

- Combines direct mapped and fully associative approaches

- Add multiple "ways" - duplicate the tag/valid/data arrays

- Each index refers to a "set" containing multiple blocks

- Called "N-way set associative" where N is number of ways

16.7.2 Two-Way Set Associative

- Two copies of tag/valid/data arrays

- Each index points to a set with 2 blocks

- Index field selects the set

- Tag comparison done in parallel within the set

- Doubles cache capacity compared to direct mapped with same number of sets

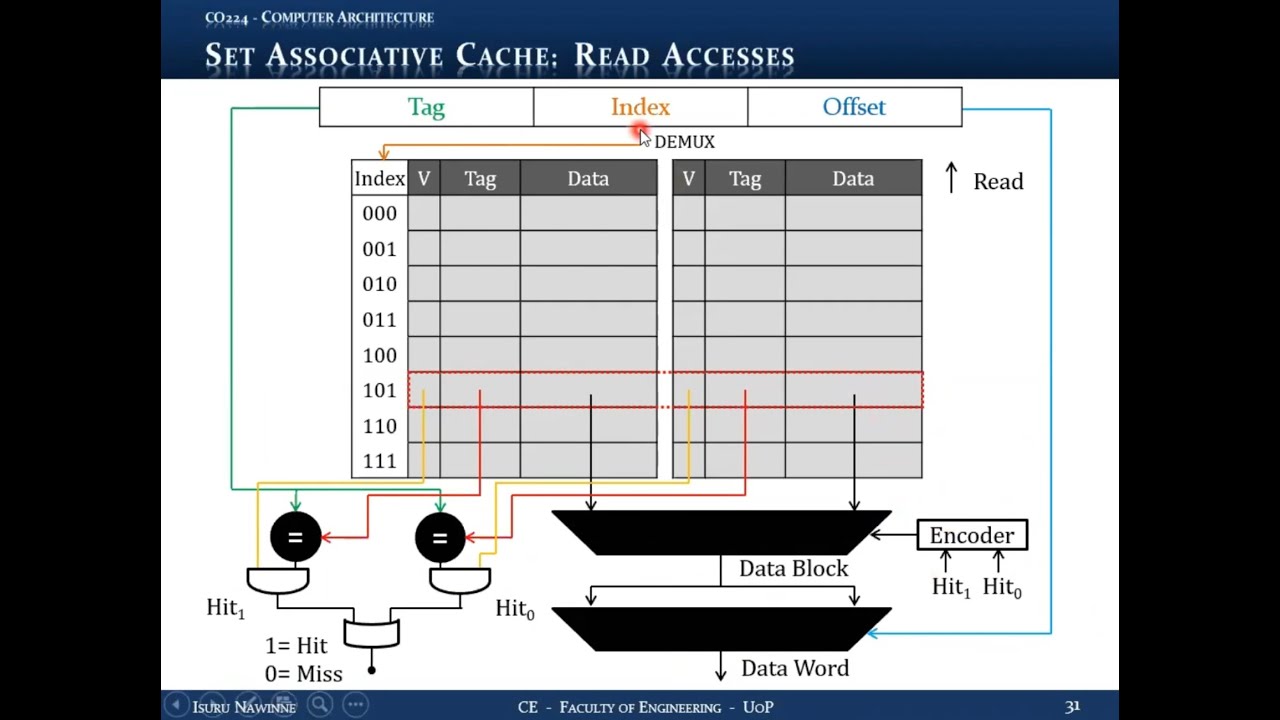

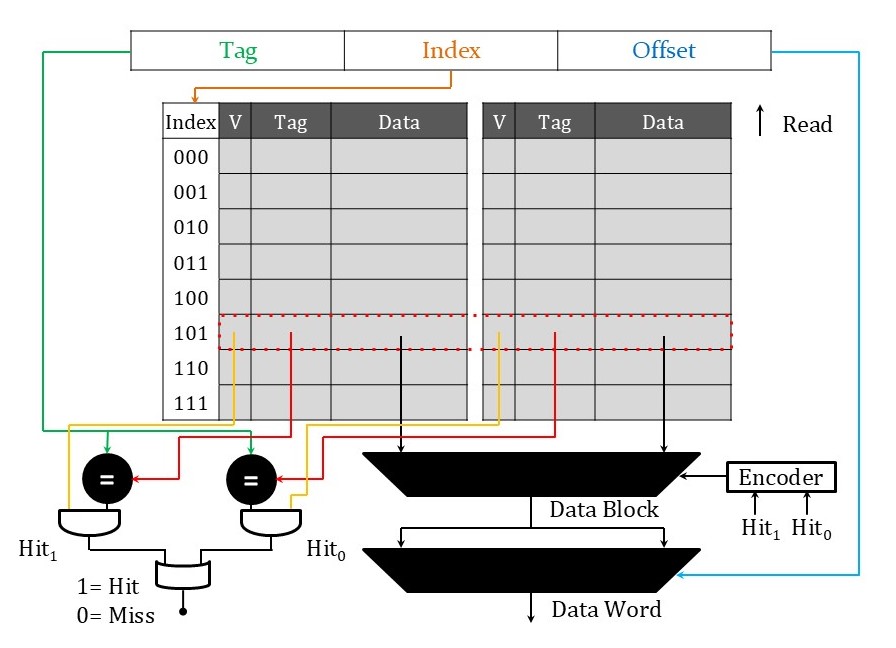

16.7.3 Read Access Process

- Use index to select correct set (via demultiplexer)

- Extract both stored tags from the set

- Parallel comparison of both tags with incoming tag

- Each way has hit status (hit0, hit1)

- Use encoder to generate select signal for multiplexer

- Select correct data block based on which way hit

- Use offset to select correct word within block

16.7.4 Important Notes

- Only one tag can match (each tag identifies unique block)

- If no tags match, it's a miss

- More complex hardware than direct mapped

- Higher hit latency due to encoding and multiplexing delays

16.8 Associativity Spectrum

16.8.1 For an 8-Block Cache, Different Organizations

- 1-way set associative (Direct Mapped):

- 8 entries, 1 way each

- 3-bit index

- Each block has fixed location

- 2-way set associative:

- 4 entries, 2 ways each

- 2-bit index

- Each set can hold 2 different blocks

- 4-way set associative:

- 2 entries, 4 ways each

- 1-bit index

- Each set can hold 4 different blocks

- 8-way set associative (Fully Associative):

- 1 entry, 8 ways

- No index field (0 bits)

- Any block can go anywhere

16.8.2 Design Considerations

- Choice depends on: program behavior, CPU architecture, performance goals, power budget

- Higher associativity → better hit rate

- Higher associativity → higher hit latency

- Higher associativity → more power consumption and cost

16.9 Associativity Comparison Example

16.9.1 Setup

- Four-block cache (4 different blocks)

- Block size = 1 word = 4 bytes

- 8-bit addresses

- Compare: Direct Mapped, 2-way Set Associative, Fully Associative (4-way)

Initial State

- All valid bits = 0 (invalid)

- All tags = 0

- Data unknown (don't care)

16.9.2 Tag and Index Sizes

- Direct Mapped: 4-bit tag, 2-bit index, 2-bit offset

- 2-way Set Associative: 5-bit tag, 1-bit index, 2-bit offset

- Fully Associative: 6-bit tag, 0-bit index, 2-bit offset

16.9.3 Memory Access Sequence

Access 1: Block Address 0

- All three caches: MISS (cold miss - first time accessed)

- All valid bits were 0

- Fetch from memory, update tag, set valid bit

Access 2: Block Address 8

- All three caches: MISS (cold miss - first time accessed)

- Tags don't match existing entries

- Fetch from memory, place in cache

Access 3: Block Address 0 (repeated)

- Direct Mapped: MISS (conflict miss - block 8 overwrote block 0 at same index)

- 2-way Set Associative: HIT (both blocks 0 and 8 fit in same set)

- Fully Associative: HIT (both blocks present)

- Demonstrates advantage of associativity

Access 4: Block Address 6

- All three: MISS (cold miss)

- 2-way: Set full, need replacement

- LRU replacement: evict block 8 (least recently used)

- FIFO replacement: would evict block 0 (first in)

- Fully Associative: Still has empty space

Access 5: Block Address 8 (repeated)

- Direct Mapped: MISS (conflict miss - keeps conflicting at index 0)

- 2-way: MISS (conflict miss - block 8 was evicted by block 6)

- Fully Associative: HIT (block 8 still in cache)

Final Score

- Direct Mapped: 0 hits, 5 misses (all misses after cold misses)

- 2-way Set Associative: 1 hit, 4 misses (one conflict miss)

- Fully Associative: 2 hits, 3 misses (only cold misses)

16.9.4 Types of Misses

- Cold Misses: First access to address (unavoidable)

- Conflict Misses: Block evicted due to mapping, accessed again later

16.9.5 Key Observations

- Higher associativity reduces conflict misses

- Fully associative eliminates conflict misses (only cold misses remain)

- But higher associativity increases hit latency and cost

16.10 Trade-Offs Summary

16.10.1 Hit Rate

- Increases with higher associativity

- Direct mapped has most conflict misses

- Fully associative has only cold misses

16.10.2 Hit Latency

- Increases with higher associativity

- More comparators, encoders, multiplexers add delay

- Direct mapped is fastest

16.10.3 Power and Cost

- Increases with higher associativity

- More hardware for parallel comparison

- More complex control logic

16.10.4 Design Decision Factors

- Application requirements

- Performance goals

- Power budget

- Cost constraints

- Embedded systems often use lower associativity (FIFO replacement)

- High-performance systems use higher associativity (PLRU replacement)

Key Takeaways

- Write policies manage cache-memory consistency:

- Write-through: Simple but generates heavy memory traffic

- Write-back: More efficient but requires dirty bit tracking

- Write buffers improve write-through performance by decoupling cache and memory writes

- Cache performance depends on three factors: hit rate, hit latency, and miss penalty

- Associativity spectrum ranges from direct-mapped (1-way) to fully associative (N-way)

- Higher associativity reduces conflict misses and improves hit rate but increases complexity

- Set-associative caches balance the trade-offs between direct-mapped and fully associative designs

- Replacement policies (LRU, PLRU, FIFO) determine which block to evict in associative caches

- Design decisions must balance performance, power consumption, cost, and complexity

- Real-world caches use different associativity levels based on application requirements

- Performance analysis shows that even small improvements in hit rate significantly reduce average access time

Summary

This lecture examines two critical aspects of cache design: write policies and associativity. Write-through and write-back policies each offer distinct trade-offs between simplicity and efficiency, with write buffers providing a middle ground that improves performance without excessive complexity. The exploration of associative cache organizations reveals how different levels of associativity—from direct-mapped through set-associative to fully-associative—affect hit rates, access latency, and hardware complexity. Through detailed performance analysis and practical examples, we discover that while higher associativity generally improves hit rates by reducing conflict misses, it comes at the cost of increased hit latency, power consumption, and implementation complexity. Modern cache systems carefully balance these competing factors, with set-associative designs emerging as an effective compromise that captures most of the benefits of full associativity while maintaining reasonable complexity. Understanding these design trade-offs is essential for optimizing memory hierarchy performance in real-world computer systems.