18.1 Introduction

Virtual memory represents one of the most elegant abstractions in computer architecture, creating a layer between physical memory hardware and the memory view presented to programs. This lecture explores how virtual memory enables programs to use more memory than physically available by treating main memory as a cache for disk storage, supports safe execution of multiple concurrent programs through address space isolation, and provides memory protection mechanisms preventing programs from corrupting each other's data. We examine page tables, translation lookaside buffers (TLBs), page faults, and the critical design decisions that make virtual memory both practical and performant despite the enormous speed gap between RAM and disk storage.

18.2 Introduction to Virtual Memory

Virtual memory allows programs to use more memory than physically available by using main memory as a cache for secondary storage.

18.2.1 Key Purposes of Virtual Memory

- Allow programs to use more memory than actually available

- Support multiple programs running simultaneously on a CPU

- Enable safe and efficient memory sharing between programs

- Ensure programs only access their allocated memory

18.3 CPU Word Size and Address Space

The relationship between CPU word size and addressable memory determines the maximum amount of memory that can be addressed.

18.3.1 Address Space by CPU Word Size

8-bit CPU

- Maximum addressable memory: 256 bytes (2^8)

16-bit CPU

- Maximum addressable memory: 64 kilobytes (2^16)

32-bit CPU

- Maximum addressable memory: 4 gigabytes (2^32)

- Became mainstream in early 1980s

- Was replaced when systems started reaching 4 GB memory limit

64-bit CPU

- Maximum addressable memory: 16 exabytes (2^64)

- About 16 million gigabytes

- Current mainstream word size

- Became mainstream around 2002-2003

18.3.2 Historical Pattern

- Maximum address space sizes were always much larger than commonly used RAM sizes

- Architectures were replaced when high-end systems started reaching the address space limits

- Personal computers typically had much less memory than the theoretical maximum

18.4 Virtual vs Physical Addresses

18.4.1 Virtual Address

- Address generated by CPU

- Refers to entire theoretical address space

- CPU thinks it has access to full address space

- In 64-bit CPU: can address up to 16 exabytes

18.4.2 Physical Address

- Actual address in real memory (RAM)

- Much smaller range than virtual addresses

- Typical modern RAM: 8-16 GB (much less than 16 exabytes)

18.4.3 Address Translation

- Virtual addresses must be translated to physical addresses

- Translation required every time memory is accessed

- Main mechanism for making virtual memory work

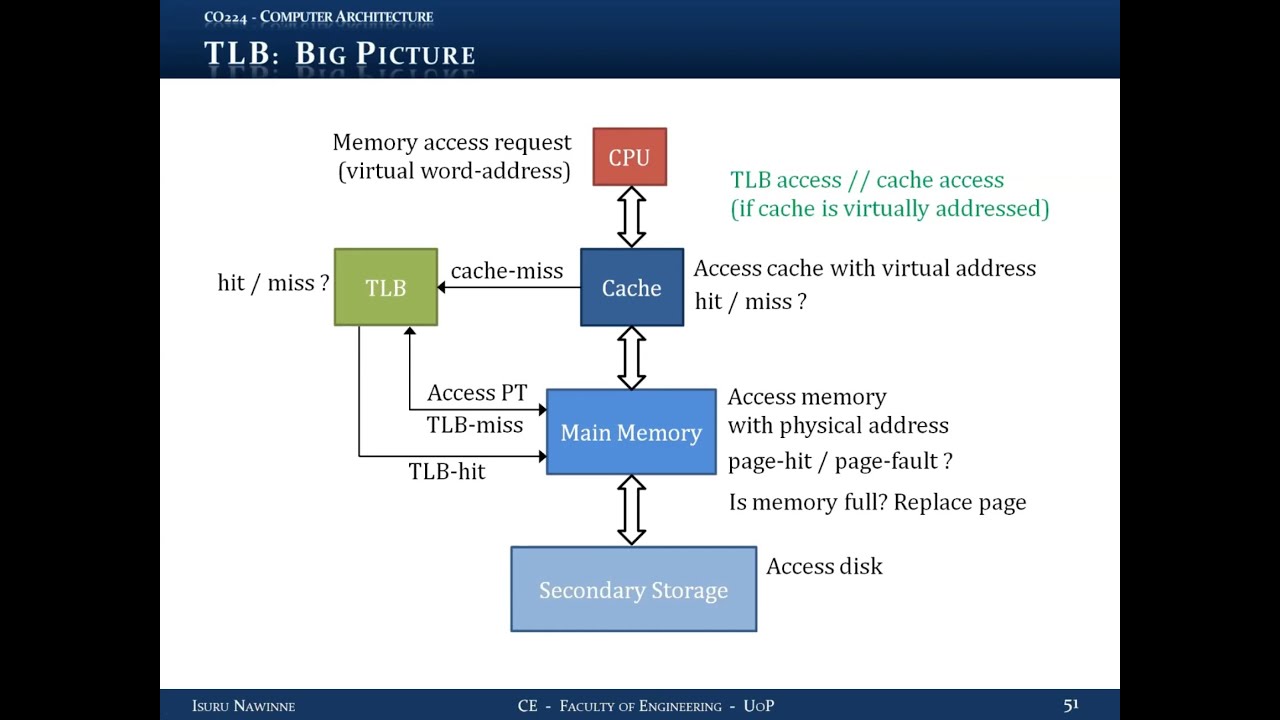

18.5 Memory Hierarchy with Virtual Memory

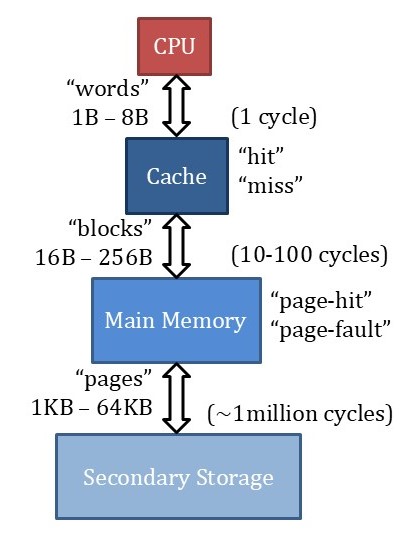

Complete hierarchy from top to bottom:

- CPU (generates virtual addresses, thinks memory is large and fast)

- Cache (virtually or physically addressed)

- Main Memory (acts as cache for secondary storage)

- Secondary Storage/Disk (contains all pages)

CPU accesses cache directly. Main memory acts as cache for disk, not just a second level cache - requires additional mechanisms.

18.6 Terminology

18.6.1 CPU Level

- Accesses: Words (1, 4, or 8 bytes)

- Hit/Miss terminology used

18.6.2 Cache Level

- Transfers: Blocks (16-256 bytes typically)

- Hit/Miss terminology used

18.6.3 Memory Level

- Transfers: Pages (1 KB to 64 KB typically)

- Page Hit: Page is present in memory

- Page Fault: Page is not present in memory (not "miss")

18.7 Access Latencies

Understanding the latency differences is crucial for virtual memory design:

- Cache Hit: Under 1 cycle

- Cache Miss (accessing main memory): 10-100 cycles

- Page Fault (accessing disk): ~1 million cycles

- Extremely large penalty

- Influences design decisions significantly

- Page faults handled in software by OS due to large penalty

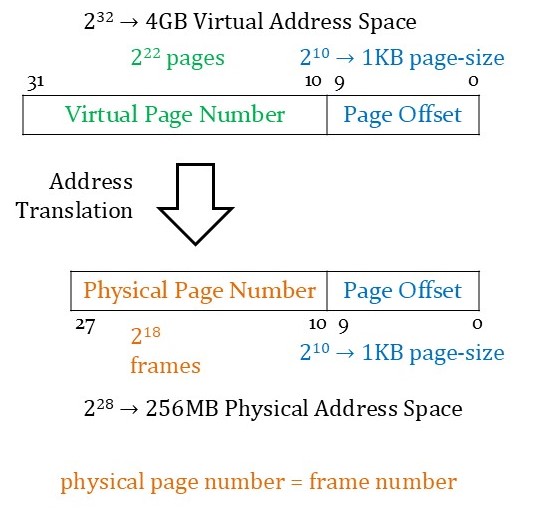

18.8 Virtual and Physical Address Structure

18.8.1 Example with 32-bit Addresses

Virtual Address (32 bits)

- Virtual Page Number: 22 bits (most significant)

- Page Offset: 10 bits (least significant)

- Virtual address space: 4 GB

- Number of virtual pages: 2^22 pages

- Page size: 2^10 = 1 KB

Physical Address (28 bits)

- Physical Page Number (Frame Number): 18 bits (most significant)

- Page Offset: 10 bits (least significant)

- Physical address space: 256 MB

- Number of frames: 2^18 frames

- Page size: 1 KB (same as virtual)

18.8.2 Key Points

- Page offset has same number of bits in virtual and physical addresses

- Physical address space is smaller than virtual address space

- Memory contains "frames" where pages can be placed

- Frame = slot in memory that can hold a page

18.9 Supporting Multiple Programs

Multiple programs can run simultaneously by sharing physical memory:

18.9.1 Each Program

- Has its own virtual address space

- Thinks it has entire memory to itself

- CPU switches between programs quickly

- Creates impression of simultaneous execution

18.9.2 Memory Sharing

- Physical memory contains active pages from all running programs

- Each program's virtual pages map to different physical frames

- Operating system ensures programs only access their own memory

18.9.3 Example

- Program 1 virtual address space: 8 virtual pages

- Program 2 virtual address space: 8 virtual pages

- Physical memory: Only 4 frames available

- Active pages from both programs share the 4 frames

- Same virtual page number from different programs can map to different physical frames

18.10 Page Table

The page table is a data structure stored in memory that contains address translations.

18.10.1 Purpose

- Stores virtual-to-physical address translations

- One page table per program

- Contains entries for ALL virtual pages (not just active ones)

18.10.2 Page Table Entry Contents

- Physical Page Number (main component)

- Valid Bit: Is the page currently in memory?

- 1 = Page is in memory (translation valid)

- 0 = Page not in memory (page fault)

- Dirty Bit: Has page been modified?

- 1 = Page modified, inconsistent with disk

- 0 = Page not modified, consistent with disk

- Additional bits: Access permissions, memory protection status

18.10.3 Finding Page Table

- Page tables stored at fixed locations in memory

- Page Table Base Register (PTBR): Special CPU register storing starting address of active page table

- When CPU switches programs, OS updates PTBR to point to correct page table

18.11 Address Translation Process

Steps to access memory:

- CPU generates virtual address (virtual page number + page offset)

- Access page table using PTBR + virtual page number as index

- Read page table entry:

- If valid bit = 0: Page fault (handled by OS)

- If valid bit = 1: Read physical page number

- Construct physical address: Physical page number + page offset

- Access physical memory with physical address

- Return data to CPU

18.11.1 Memory Accesses Required

- One access for page table

- One access for actual data

- Total: Two memory accesses per data access

18.12 Page Table Size Calculation

18.12.1 Example: 4 GB Virtual, 1 GB Physical, 1 KB Pages

Number of Entries

- Virtual address: 32 bits

- Page offset: 10 bits (for 1 KB pages)

- Virtual page number: 22 bits

- Number of entries: 2^22 = ~4 million entries

Entry Size

- Physical address: 30 bits (for 1 GB)

- Page offset: 10 bits

- Physical page number: 20 bits

- Valid bit: 1 bit

- Dirty bit: 1 bit

- Total needed: 22 bits

- Actual storage: 32 bits (word-aligned)

- Size per entry: 4 bytes

Total Page Table Size

- 4 bytes × 2^22 entries = 16 MB

- Significant memory overhead for each program

18.13 Write Policy for Virtual Memory

18.13.1 Write-Through: NOT USED

- Would require writing to disk on every write

- 1 million cycle penalty unacceptable

- Not a good design decision

18.13.2 Write-Back: USED (Standard Policy)

- Writes only update memory

- Dirty bit tracks modified pages

- Only write to disk when:

- Page is evicted from memory

- Page's dirty bit is 1

- Minimizes disk accesses

18.14 Placement Policy

18.14.1 Fully Associative Placement

- Any page from disk can go to any frame in memory

- Memory treated as one large set containing all frames

- No direct mapping or set restrictions

- Maximizes flexibility in page placement

- Reduces page faults

18.14.2 Why Fully Associative?

- Minimizes page faults (primary goal)

- Large page fault penalty (1 million cycles) justifies complexity

- Different from cache (doesn't use tag comparators in memory)

- Address translation through page table provides necessary mechanism

18.15 Page Fault Handling

18.15.1 What Operating System Must Do

1. Fetch Missing Page

- Access disk to retrieve page

- OS must know disk location of page

- OS maintains data structures tracking page locations

2. Find Unused Frame

- OS tracks which frames are currently used

- Can determine this through page tables

- If unused frame exists: Place page in unused frame

3. If Memory Full (No Unused Frames)

- Select active page to replace using replacement policy

- Common replacement policies:

- Least Recently Used (LRU)

- Pseudo-LRU (PLRU)

- First-In-First-Out (FIFO)

- Least Frequently Used (LFU)

- Goal: Exploit temporal locality (keep recently/frequently used pages)

4. Check Dirty Bit of Page to be Replaced

- If dirty bit = 1: Write page back to disk before replacement

- If dirty bit = 0: Can directly overwrite (data consistent with disk)

- Prevents data loss

5. Update Data Structures

- Update page table entry for new page

- Update page table entry for replaced page (set valid = 0)

- Place fetched page in frame

18.15.2 Optimization

- Many operations can occur in parallel during disk fetch

- While fetching data, OS can determine placement and handle replacement

- Use buffers for write-back operations

18.15.3 Why Software Handling?

- 1 million cycle penalty is so large that software overhead is negligible

- Complex replacement policies better suited to software

- Hardware optimization doesn't provide significant benefit

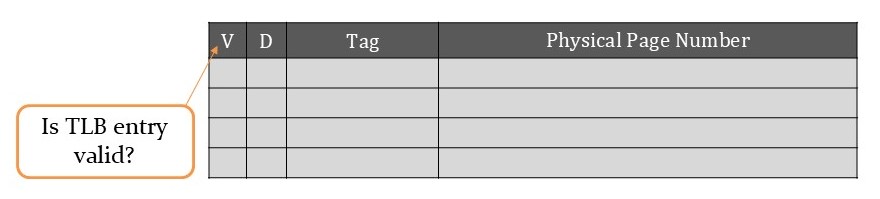

18.16 Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

18.16.1 Purpose

- Avoid accessing memory twice for every data access

- Act as cache for page table entries

- Reduce address translation overhead

18.16.2 What is TLB?

- Hardware cache specifically for page table entries

- Stores recently used address translations

- Based on locality of page table entry accesses

- Exploits temporal and spatial locality of page accesses

18.16.3 TLB Entry Structure

- Tag: Virtual address tag (or physical address tag)

- Physical Page Number: The address translation

- Valid Bit: Is this TLB entry valid?

- Different from page table valid bit

- Indicates if TLB entry contains valid translation

- Dirty Bit: Same meaning as in page table

18.16.4 TLB Parameters

Size

- 16-512 page table entries (typical range)

Block Size

- 1-2 address translations

- Small blocks because spatial locality between pages is larger

- Adjacent pages not as closely related as adjacent cache blocks

Placement Policy

- Fully associative or set associative

- Fully associative for smaller TLBs (~16 entries)

- Set associative for larger TLBs

- Goal: Keep miss rate below 1%

Hit Latency

- Much less than 1 cycle

Miss Penalty

- 10-100 cycles (memory access required)

18.16.5 TLB Operation

Hit

- Address translation available in TLB

- Use translation directly without accessing memory

- Only one memory access needed (for data)

Miss

- Translation not in TLB

- Must access page table in memory

- Total: Two memory accesses (page table + data)

18.16.6 Why Low Miss Rate Essential?

- TLB misses double memory access time

- Must access page table (10-100 cycles) then data

- Miss rate typically kept below 1%

- > 99% of translations served by TLB

18.17 Complete Memory Access with TLB

Two different approaches for handling memory access with TLB:

18.18 Approach 1: Virtually Addressed Cache

18.18.1 Process

- CPU generates virtual address

- Access cache with virtual address (parallel with TLB)

- Cache Hit: Return data to CPU immediately

- Cache Miss:

- Check TLB for address translation

- TLB Hit:

- Get physical address

- Access memory with physical address

- Fetch missing block

- Update cache

- Send word to CPU

- TLB Miss:

- Access page table in memory

- Page Hit:

- Get translation

- Access memory for data

- Update TLB

- Update cache

- Send word to CPU

- Page Fault:

- OS accesses disk

- Fetch missing page

- Find unused frame or replace page

- If replaced page dirty: write back

- Update page table

- Update TLB

- Update cache

- Send word to CPU

18.18.2 Advantage

- TLB access overlapped with cache access

- Both happen in parallel

- No additional latency for TLB access on cache hit

18.19 Approach 2: Physically Addressed Cache

18.19.1 Process

- CPU generates virtual address

- Access TLB for translation first

- TLB Hit:

- Get physical address

- Access cache with physical address

- Cache Hit: Return data to CPU

- Cache Miss:

- Access memory with physical address

- Fetch missing block

- Update cache

- Send word to CPU

- TLB Miss:

- Access page table in memory

- Page Hit:

- Get translation

- Update TLB

- Access cache with physical address

- If cache hit: return data

- If cache miss: fetch from memory, update cache, return data

- Page Fault:

- OS handles as described above

- Update page table, TLB, cache

- Return data to CPU

18.19.2 Advantage

- Cache physically indexed and tagged

- Simpler cache design

- No aliasing issues

18.19.3 Key Difference

- Approach 1: Cache uses virtual addresses, TLB access parallel

- Approach 2: Cache uses physical addresses, TLB access sequential

Both approaches are valid, and the choice depends on cache indexing method (virtual vs physical).

Key Takeaways

- Virtual memory provides memory abstraction and protection

- Address translation is fundamental to virtual memory operation

- Page tables map virtual addresses to physical addresses

- TLB caches translations to avoid double memory access

- Page faults are extremely expensive (~1 million cycles)

- Write-back policy is essential for virtual memory

- Fully associative placement minimizes page faults

- Multiple programs can safely share physical memory

- OS handles page faults in software

- Virtual memory enables modern multitasking operating systems

Summary

Virtual memory represents a crucial abstraction in modern computing, enabling efficient and safe memory management across multiple concurrent programs while providing each program with the illusion of abundant, dedicated memory resources.